Data Isn’t Transparency: Why USASpending.gov Buried the Truth (and DOGE Dug It Up)

An explanation of data indexing and why critics like Mark Cuban are misguided.

A common critique of DOGE is: "Why does this matter? The spending data was already available on USASpending.gov! Why didn’t anyone pay attention before?" Prominent figures like Mark Cuban have echoed this criticism.

This criticism reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how databases and data indexing work. The raw data has always existed, but accessibility is what transforms information into insight. That’s why I built award search and name search on DataRepublican.com—to make the data searchable, useful, and actionable.

This article will explain data indexing and why it’s crucial for making complex datasets meaningful. While I’ll cover some technical details, I’ll keep the explanation as high-level as possible so that anyone—regardless of technical background—can follow along.

A Bible Analogy for Data Indexing

To illustrate the importance of indexing, let’s use a familiar analogy: the Bible.

Imagine the Bible was a single, continuous scroll with no divisions—no books, no chapters, no verses. Now, suppose you wanted to find the Sermon on the Mount. Without structure, you’d be forced to scan through an enormous block of text, making it incredibly time-consuming to locate what you need.

This is precisely the problem that data indexing solves. Indexing is what enables rapid access to relevant information, transforming an overwhelming mass of data into something searchable and usable.

In the rest of this article, I’ll explain how indexing works and how I applied these principles to make government spending data more accessible.

Book Pages, or N-ary Storage Model

Every physical book contains a basic form of an index: page numbers. These numbers allow us to quickly locate information within a book, providing structure and order to the content.

Similarly, most traditional databases—including PostgreSQL, the database system behind USASpending.gov—use a concept called pagination to manage data storage. Data is written in pages, which are contiguous chunks of storage space. Just as sentences are written sequentially across book pages, rows in a database are written sequentially or in an append order. This is known as the N-ary Storage Model (NSM).

How Data is Stored in Pages

In an NSM database, data is stored in pages that are filled sequentially:

A full page can no longer accommodate new rows.

A partially full page has space for additional rows.

An empty page is available for new data.

If a new row is inserted, it will be written into the first available free space—just as a book continues filling its pages in reading order. The diagram below illustrates this concept:

1️⃣ Page 1: Full—no space left for new rows.

2️⃣ Page 2: Partially full—new data can still be added.

3️⃣ Page 3: Empty—ready to be written to.

If a fourth row needs to be inserted, it will be added to the next available spot in Page 2 before moving on to Page 3. This ensures that rows are stored in sequence, just as sentences in a book are arranged in the order they are meant to be read.

Retrieving Information: The Challenge

Imagine you’re searching for a specific sentence in a book. If the book is well-structured, you can say, "Find me the second sentence on page 10." A person can quickly turn to that page and locate the sentence because the book is inherently organized for fast lookups based on page numbers.

A similar principle applies to NSM databases like USASpending.gov. If you have a row identifier, you can request a specific row directly—just as you’d look up a sentence by page number. However, in many cases, these row identifiers are not publicly exposed. This means additional indexes must be created to make data retrieval practical for real-world queries.

B-Tree Indexes in PostgreSQL: A Book Analogy (and Why They’re Bad for Text Search)

Imagine you're in a library looking for a book. Libraries organize books alphabetically by title or numerically by catalog number so you can quickly locate what you need. But what if you weren’t looking for a specific title—what if you needed to find a particular sentence buried somewhere inside an unknown book?

Suddenly, the catalog system is useless. You’d have to open every book and scan every page just to find your sentence.

This is exactly why B-tree indexes—the default indexing system in PostgreSQL—work great for structured data (like book titles or catalog numbers) but fail when searching unstructured text (like finding a word hidden deep inside a paragraph).

Let’s break this down.

How B-Tree Indexes Work (Like a Library Catalog)

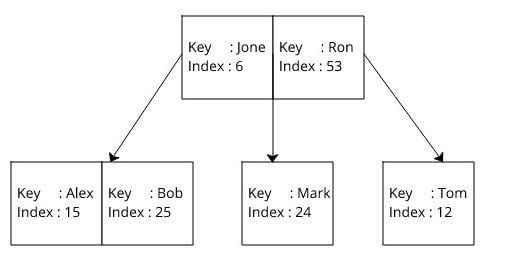

A B-tree (Balanced Tree) index is like an alphabetically sorted library catalog. Each entry in the catalog points to a specific book on the shelf, allowing for quick lookups when searching for:

✅ An exact match (e.g., "Find me The Great Gatsby")

✅ A range of values (e.g., "Show me all books by authors whose last names start with ‘A’ through ‘C’")

✅ Prefix-based searches (e.g., "Find books that start with ‘Harry Potter’")

In PostgreSQL, B-trees work the same way. If you have a column like title, a B-tree index makes this query fast:

SELECT * FROM books WHERE title = 'The Hobbit';Or this:

SELECT * FROM books WHERE title LIKE 'Harry Potter%';Both queries are efficient because B-trees store data in sorted order and allow for fast prefix lookups—just like a well-organized library catalog.

But what if you wanted to do a text search, like search for “frogs” in awards in USASpending.gov? B-Tree indexes fall apart.

SELECT * FROM awards WHERE description LIKE '%frogs%';The % at the beginning means the database has to scan every single row in the table, just like manually flipping through every book in a library to find a hidden sentence.

In short, you cannot use traditional B-tree indexes to do text searches of spending awards in USASpending.gov. This is where DataRepublican.com comes in.

DataRepublican’s Approach: A Reverse (Inverted) Index

To solve the text search problem, DataRepublican.com builds a dual layer reverse index—sometimes called an inverted index—for every searchable column. Rather than storing rows in B-trees, the site processes the entire dataset to build a keyword → list of matching rows map.

Here’s the conceptual flow:

Chunking: The federal grants dataset is split into batches (e.g., CSV files named award_batch_000.csv, award_batch_001.csv, etc.) so it’s manageable in size.

Tokenization: Each piece of text—award descriptions, recipient names, etc.—is split into smaller words (tokens). Punctuation and common symbols are removed, and everything is lowercased.

Inverted Index: For every unique token (e.g., “unaccompanied,” “refugee,” “solar,” “Smith”), the system records all row IDs in which that token appears. This creates lines like:

unaccompanied: 1,8,19,...

refugee: 1,12,53,...

...These “reverse index” files allow the website to jump straight to the rows that match a given word.

Prefix Matching (Optional): DataRepublican can also handle partial words if you check “Enable prefix search.” It does this by scanning for tokens that start with a user’s typed keyword. That’s still far more direct than scanning every row in a table because the indexing structures specifically track these prefixes.

Performing a Search

When a user enters keywords, DataRepublican.com does the following:

Read the Reverse Index: Each typed word looks up its matching rows in the corresponding award_reverse_index.txt.

Intersect Results: If multiple keywords are used (e.g., “community” and “grant”), the system intersects the sets of row IDs so only rows containing all keywords are returned.

Load the Matching Rows: Once it has the row IDs, the site fetches the relevant portions of the CSV data—no scanning from top to bottom necessary.

Display: The user sees only the relevant results, along with extra details like sums of award amounts.

This method acts like the “Index” at the back of a book—jumping directly to relevant pages instead of flipping through everything.

This is the key reason why you can type in a single word (like “refugee”) or several keywords (like “community grant” or “health program solar”) on DataRepublican.com and actually get instant, narrowed-down results—no more wading through a monolithic database on your own.

The Core Fallacy: Confusing Data Existence with Data Accessibility

The critique that DOGE is just "pulling numbers from USASpending.gov and repackaging them" fundamentally misunderstands the difference between raw data availability and data accessibility.

USASpending.gov does indeed host federal spending data, but it does so in a format that:

Relies on B-tree indexes, meaning searches are limited to exact or prefix-based matches (not general keyword searches).

Has an overwhelming, clunky interface designed for specific pre-filtered queries, not for exploratory discovery or investigative research.

DataRepublican.com took that raw, buried data and made it instantly searchable through a custom-built inverted index that allows full-text search across over a hundred thousand active awards. That’s not just repackaging—it’s solving a major usability problem that USASpending.gov itself failed to address.

This Is Not a New Concept—It’s the Foundation of Search and Innovation

By the logic of critics, Google Search never "discovered" anything new either—after all, every web page they index was already public, right? So should we dismiss Google's impact on information accessibility?

Google didn’t invent web pages; it made them searchable.

DataRepublican.com didn’t invent government spending data; it made it discoverable.

There is a vast difference between raw, difficult-to-access information and structured, accessible, and actionable insights. The latter is what drives transparency, accountability, and public engagement.

Conclusion: Data Accessibility Matters

The problem was never that the data didn’t exist—it was that no one could easily find it. By enabling full-text search, pattern recognition, and investigative workflows that USASpending.gov does not, DataRepublican.com actually democratized access to critical financial data.

Dismissing this effort is not just ignorant—it reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how information retrieval, search technology, and transparency actually work.

I follow you on X as well. Thank you for explaining your work! I wish I had your talent.

DR - that is fantastic, thank you.

I love the Plain English about Google and web sites - that resonates. We need to get that to X and broadcast it.

Well done!